Chapter 1: A Building of Beginnings

Design & Construction of the British Military Hospital (BMH)

In the 1930s, the new BMH was planned and constructed during peacetime to serve the Army, Navy, and Royal Air Forces in Singapore. As Japanese aggression increased prior to World War II, there was a build-up of 19 British battalions in the Malaya region.

With a continuing influx of troops, it became apparent that more medical facilities were needed for British military personnel and their families than could be provided at Tanglin Barracks—more serious cases were sent to the General Hospital.

The Indian Army had its own military hospital in Tyersall Park while the Malay Regiment and the Sappers (Corps of Royal Engineers) were admitted to the hospital on Pulau Belakang Mati.

After the BMH was opened, the Tanglin Military Hospital was set aside for special cases.

The location of the old barracks hospital, now occupied by Alexandra Hospital’s football field.In the early 1900s, the British set up Alexandra Barracks near Alexandra Road. Established by the British in 1864, Alexandra Road was officially named after Queen Alexandra, the consort to King Edward VII. Alexandra Road connected Pasir Panjang to River Valley. The cantonment was served by a camp hospital that, according to a 1910 map, was built of Bintangor poles, wood, and attap—except for its cook houses and latrines, which were built of brick and tiled roofs.

The camp hospital, built on the site of the current hospital’s football field, had a general ward, malarial wards, isolation wards, a dispensary, an office, a mortuary, an oil store, a fire engine, a bathing enclosure, staff quarters, cook houses, boilers, and an incinerator. It was demolished some time in the early 1920s.

In 1938, construction of the British Military Hospital began on the camp hospital site that used to serve the Alexandra cantonment. The designated site was a 32-acre (12-hectare) plot of land close to Ayer Rajah Road (the present-day Ayer Rajah Expressway) and the Federated Malay States Railway (FMSR) tracks so that people could be transported for treatment quickly.

The FMSR was later renamed the Malayan Railway Administration (MRA) in 1948 and formally rebranded again as the Keretapi Tanah Melayu Berhad (KTMB)—its current name—in 1962. Ayer Rajah Road was only a track then, and what is Alexandra Village today was a row of shops and attap shanties that sprang up to serve the hospital staff.

Designed and constructed by a team of Royal Engineers supervised by Chief Draughtsman Major J. W. Colbran, the new military hospital was to be a principal military hospital for the Malayan region.

In 1938, it was hailed in The Straits Times as “the most up-to-date and one of the largest military hospitals outside Great Britain.” The BMH was a “modern new three-storeyed block, with [a] basement… [and] expected to be completed by July 1939.” It aimed to rank among the finest military hospitals in the world. The new hospital claimed to be “equipped with the latest equipment and [to] embody all the most modern ideas of hospital construction.”

The essay “Military Hospitals—Choice of Site and Design” by Major P. N. Walker-Taylor, published in the Journal of Royal Army Medical Corps in 1940, stated that his formulations “… apply both at home and abroad, for after all the object of hospitals, curing the sick, does not differ all over the world, and generally the methods do not vary overmuch either; therefore, if an efficient design for a hospital of specific size and nature (say a general hospital of 600 beds) can be decided upon for one region, it should prove effective, with minor variations due to climate, etc., for other regions as well.”

The Royal Engineers’ planning and design of the BMH could be described as a “culmination of more than a century of heterogeneous engineering.” The main hospital blocks (present-day Blocks 1 to 7) share the characteristics of tropical “pavilion plan” hospitals, including those of the Singapore General Hospital (1926) and Tan Tock Seng Hospital (1909). Pavilion plan principles originated in 18th century France and were made popular in England by John Roberton and George Godwin in the mid-19th century.

Part Two

Did You Know?

The Tanglin Military Hospital was later converted into what we know today as Dempsey Hill, home to numerous food and beverage outlets!

The design of the roomy three-storey barracks block (present-day Block 29) likely adopted building norms documented in the tropical categories of the Barracks Synopsis, a set of standards issued by the War Office. The standards distilled detailed architectural practices that had been iteratively refined since its first edition in 1865, gleaned from experiences in tropical stations ranging from the West Indies to India.

The BMH barracks block shared characteristics with the barracks from the 1930s Changi Cantonment and Gillman Barracks, which were planned according to the same standards. By adapting these standards to local contexts and using prefabricated components sent from the metropole, the British empire was able to build and maintain quality buildings at scale over long distances and in unfamiliar territories.

According to former staff member Lloyd Hughes, “the foundations were started in late 1938, but the building itself was not completed until well into 1939. … This included the accommodation block, that is, the barrack rooms and married quarters, also other buildings for cook-house staff and a sergeant’s mess … in all, the Alexandra hospital was quite a big job.”

Between 1938 and 1940, most of the main building and ancillary blocks were constructed before the opening of the hospital. Quarters for the staff were first built across the railway line in Alexandra Park. Eventually, officers’ quarters and mess, nursing sisters’ quarters and mess, and various other support buildings for the hospital were built in Alexandra Park.

The underlying rationale was that, with improved ventilation, the mortality rate (at that time exceedingly high) would be significantly reduced. Among the enthusiasts for this new style was Florence Nightingale (herself a proponent of the miasma theory), who had observed astronomically high death rates in the hospital at Scutari during the Crimean War (1854–6).

The pavilion plan was first put forth for military hospitals in the British Army’s tropical colonies as early as 1863, according to the Reports of the Barrack and Hospital Improvement Commission for Indian Stations, as well as the 1864 Report of the Royal Commission on the Sanitary State of the Army in India. Its principles include considerations for light, ventilation, and coolness, which were perceived to reduce mortality rates.

Designed and constructed by a team of Royal Engineers supervised by Chief Draughtsman Major J. W. Colbran, the new military hospital was to be a principal military hospital for the Malayan region.

In 1938, it was hailed in The Straits Times as “the most up-to-date and one of the largest military hospitals outside Great Britain.” The BMH was a “modern new three-storeyed block, with [a] basement… [and] expected to be completed by July 1939.” It aimed to rank among the finest military hospitals in the world. The new hospital claimed to be “equipped with the latest equipment and [to] embody all the most modern ideas of hospital construction.”

The essay “Military Hospitals—Choice of Site and Design” by Major P. N. Walker-Taylor, published in the Journal of Royal Army Medical Corps in 1940, stated that his formulations “… apply both at home and abroad, for after all the object of hospitals, curing the sick, does not differ all over the world, and generally the methods do not vary overmuch either; therefore, if an efficient design for a hospital of specific size and nature (say a general hospital of 600 beds) can be decided upon for one region, it should prove effective, with minor variations due to climate, etc., for other regions as well.”

The Royal Engineers’ planning and design of the BMH could be described as a “culmination of more than a century of heterogeneous engineering.” The main hospital blocks (present-day Blocks 1 to 7) share the characteristics of tropical “pavilion plan” hospitals, including those of the Singapore General Hospital (1926) and Tan Tock Seng Hospital (1909).

Pavilion plan principles originated in 18th century France and were made popular in England by John Roberton and George Godwin in the mid-19th century. The underlying rationale was that, with improved ventilation, the mortality rate (at that time exceedingly high) would be significantly reduced. Among the enthusiasts for this new style was Florence Nightingale (herself a proponent of the miasma theory), who had observed astronomically high death rates in the hospital at Scutari during the Crimean War (1854–6).

The pavilion plan was first put forth for military hospitals in the British Army’s tropical colonies as early as 1863, according to the Reports of the Barrack and Hospital Improvement Commission for Indian Stations, as well as the 1864 Report of the Royal Commission on the Sanitary State of the Army in India. Its principles include considerations for light, ventilation, and coolness, which were perceived to reduce mortality rates.

Architecture of the BMH

“

In Early September 1940, Shanghai was evacuated and we found ourselves roughing it on a small coastal steamer, the S. S. Hosang, on our way back to Singapore. We arrived at Keppel Harbour in that same month and were conveyed by lorry along Alexandra Road to the entrance of the hospital. At that time the entrance was little more than a break in the hedge of hibiscus and various trees. There were two concrete posts but no notice indicating what that shiny, modern building was on the small rise.”

—Recollections of Will Brand, a medic who joined the 32nd Company, Royal Army Medical Corps (32 RAMC) at the newly erected BMH in September 1940 after a brief stint at the British Military Hospital in Shanghai.

The original buildings of the BMH were built from reinforced concrete with infill walls of local bricks. The main hospital block expressed a stripped neoclassical aesthetic with an institutional feel softened by an abundance of flowering shrubs and trees.

A long central corridor connected the pavilion-like wards of the BMH. These wards were arranged perpendicular to the corridor and isolated from the rest of the hospital.

To facilitate coolness and ventilation, the longer sides of the BMH pavilion blocks were shaded by deep tiled eaves and an additional layer of louvre windows that allowed for air passage while moderating sudden gusts.

Ten-feet-wide verandahs lined the perimeter of the wards, providing a breezy buffer and shielding the wards from direct sun. Even the verandah parapets were made porous by the use of precast, cross- braced balustrades. Windows on the wards’ longer sides faced each other to let in daylight and air, and enable cross ventilation. To prevent the formation of still air, inner and outer walls were fitted with vents and louvre windows.

Standards from the Barracks Synopsis that were applied to the BMH include ten-feet-wide verandahs enveloping the barracks with at most two corners for bath and facilities, usage of the ground floor for something other than sleeping quarters (like a dining room, recreation room, and sergeants’ canteen), usage of upper floors for sleeping quarters, and generous floor-to-ceiling heights.

The barracks also held 80 iron beds, with wooden cupboards, metal lockers, and mosquito nets on each floor. Ancillary buildings were built in 1940 to the north and west of the hospital block. These included a chapel (present-day Block 4), stores (present-day Blocks 5 and 6), offices (present-day Block 6), married quarters (present-day Block 22), and a mortuary (present-day Block 26).

A pathology laboratory (present-day Block 24) was also attached to the hospital where pathological research and examinations were carried out to safeguard the service personnel from disease and infection.

These ancillary buildings shared common architectural features, such as verandahs, tiled roofs with generous eaves, vents, and porous balustrades for ventilation and coolness. The commander’s house (present-day Block 18) was a two-storey, compact, and symmetrical stripped neoclassical-style bungalow.

It had a hip roof with a double set of extended tiled eaves, brick window sills, Tuscan columns and cornices influenced by European stripped neoclassical architecture, and a covered walkway at the rear that linked to an outbuilding, which could have been servants’ quarters.

A football field was used for parades and formal tournaments—sporting was such a popular pastime amongst British troops in pre-war Singapore that standings were published in the Army Royal Engineers Journal.

The basement of the hospital, lined with brick walls, extended for hundreds of metres underneath the main hospital block. It was equipped with electrical supply and air shafts, and likely built as a shelter to keep people and medical supplies safe from air raids. Its tunnels connected to spacious rooms that could have served as underground emergency operating theatres.

The construction cost more than $1,000,000. The design included special anti-mosquito drainage costing approximately $20,000,37 sound-dampening rubber floors, and portable X-ray units that could be transported to any department or room in the building.

Opening & Early Days of the BMH

The hospital opened on 19 July 1940 when the 32nd Company, Royal Army Medical Corps (32 RAMC) was transferred from the smaller Tanglin Barracks hospital. A week after the opening, the local newspaper wrote “[i]t is hoped that important research work will be carried out in the modern laboratory … [and that the] opening of the hospital will to some extent relieve the recent congestion in the General Hospital, Singapore.”

Private Leonard Walter Knott was posted to Singapore with the 32 RAMC around 1939/1940. He worked in the old Tanglin Military Hospital and later the new BMH as a medical orderly and pharmacy assistant. Soon after beginning his posting at the new BMH in Alexandra, he wrote in a letter to his brother: “This week is the tenth week I’ve been here and the fourth at this hospital. Previously I’d been at Tanglin but it’s [a] very old and absolutely antiquated hospital, when this place opens as it will in about five weeks, it will be a general hospital and deal with practically everything and we hope with a reasonable chance of curing the patients…”

View of the main store and Laboratory (in foreground) and western wing of the hospital (in background with red cross on roof).

View of the main store and Laboratory (in foreground) and western wing of the hospital (in background with red cross on roof).

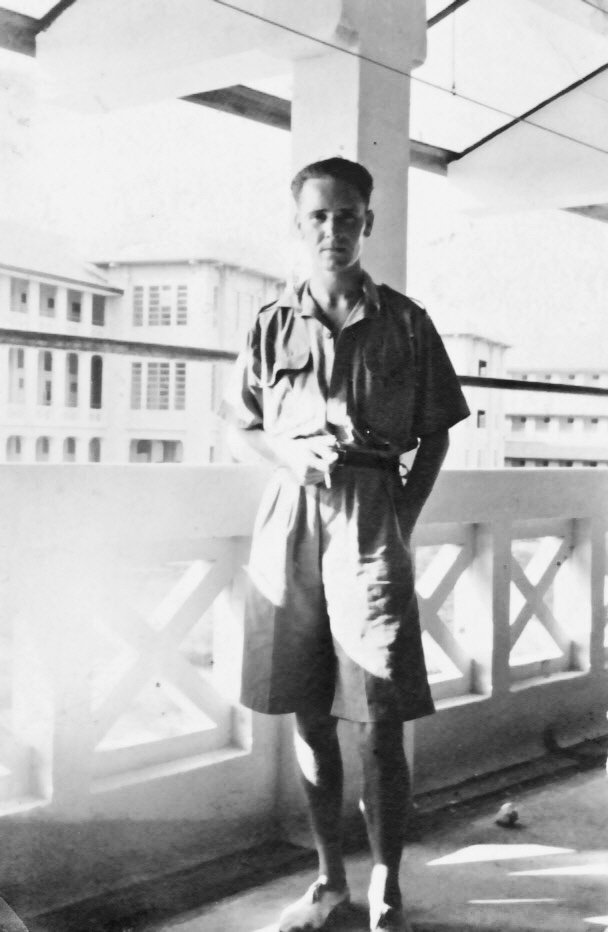

Leonard Knott standing outside of his bunk at the NAAFI canteen block.

British healthcare professionals were posted to the new hospital from their stations across the British Empire. It was announced that over 30 British sisters and nurses, including one principal matron and an assistant matron, would be brought to Singapore under the Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), but they did not arrive until late 1940.

Recreation rooms were included for patients to play indoor games and enjoy concerts on their own stage by regimental concert parties.

The city’s kampongs lay just outside the hospital and were visited by the staff and residents of the BMH.

As Will Brand recalls: “Tall trees and coconut palms hid our northern view, but 50 yards or so along the Alexandra Road there were small Chinese kampongs [villages] and a very interesting general dealer shop made of bamboo and atap, chock-a-block full of weird and wonderful things to our unaccustomed eyes. Smells too. During the day, we could buy from a stall outside the shop giant pineapples at five cents each.

There were plantations of pineapples, papaya, and towgay (bean sprouts) between the hospital and oil tanks.”

“I and my two closest friends frequently walked around the area, being interested in the local people and their activities. The land opposite the hospital on the other side of the Alexandra Road contained old rubber plantations and coconut groves. There were many kampongs occupied mainly by Chinese but with some Malays and Indians.”

On the brink of World War II in 1941, however, the original design intent had to be compromised— when a shortage of beds was anticipated, plans to increase capacity from 356 to 550 beds were approved. In the midst of the war in February 1942, the BMH reportedly packed up to 900 patients, some of whom had to be housed on stretchers in the verandahs or any other available spaces.