Chapter 2: Hardship and Heroism

Stories of Kinship

Part Two

In times of war and crisis, kinship becomes a recurring and powerful theme of the everyday. While individual experiences differ, many form networks of social relations to build a support system to cope with the traumas of war.

When the Japanese troops first invaded the hospital, numerous patients rallied to maintain hospital operations. To mitigate water shortages, a patient collected tins to store water by running back and forth through the deserted wards on the top floor of the hospital.

Others prepared and distributed meals cooked in their wards, making the most of bully beef biscuits, as well as ingredients like stale bread, butter, powdered milk, and sugar, which were made into bread pudding.

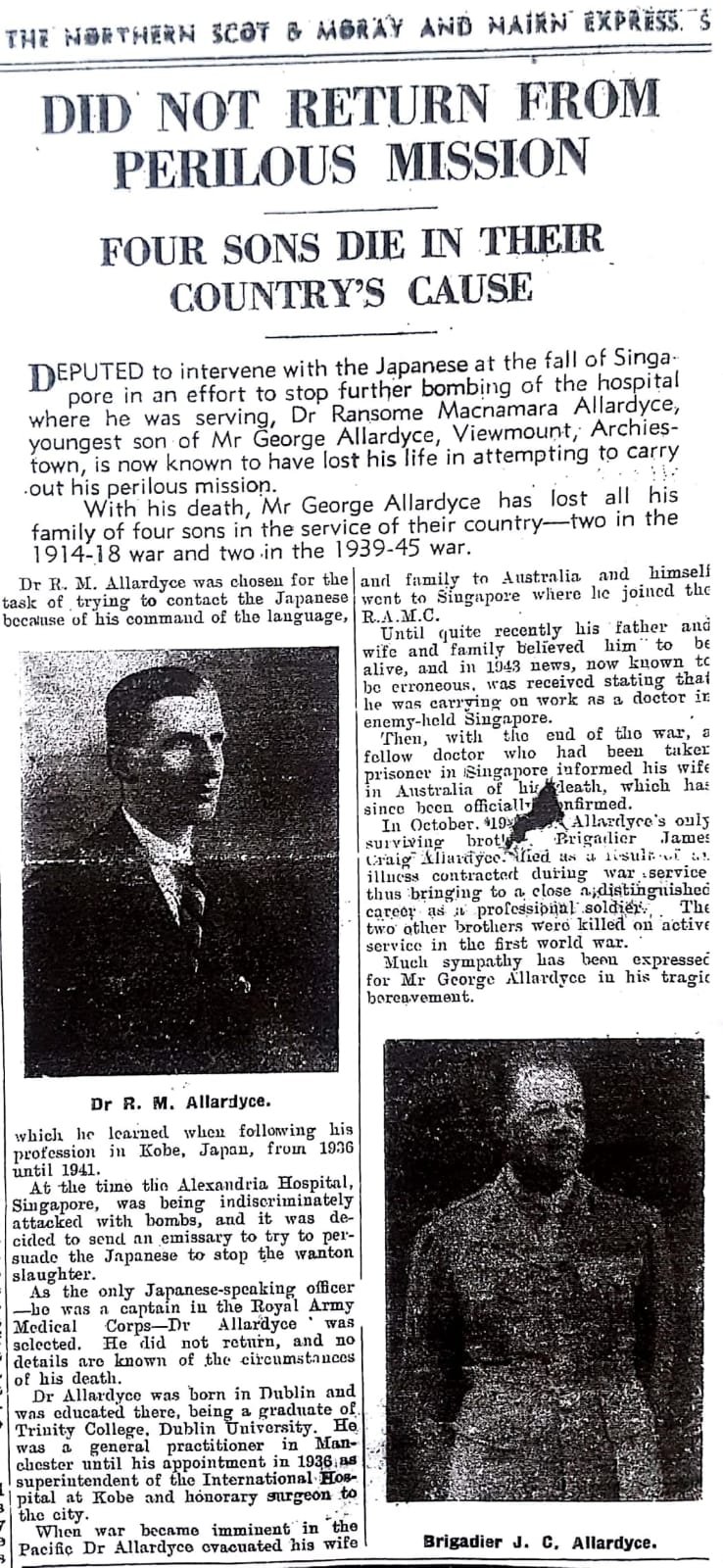

While communities were being built, elsewhere, others experienced loss and separation from their families. For the Allardyce family, Remembrance Day became an important occasion for them to honour family members who had lost their lives in both the First and Second World Wars—Captain Ransome McNamara Allardyce and his three brothers.

When the Japanese troops first broke into the hospital, Captain Allardyce volunteered to reason with the soldiers as he was the only person who could speak some Japanese, due to his prior role as the superintendent of the International Hospital in Kobe. He was never seen again.

Pictures depicting Captain Ransome Macnamara Allardyce in various stages of his life, (from left) as a young doctor, (middle) with his wife Madeleine, son George, daughters Gene and Anne at their residence in Yamamoto-dori, Kobe, in western Japan, (right) and in a newspaper article detailing the demise of four Allardyce sons including Ransome, to war.

Like the Allardyces, many were forced to part from their closest kin during the massacre. On 12 February, a handful of nurses were evacuated from the British Military Hospital by ship. The hospital’s administration intended to only maintain a skeleton staff of around 200 medical personnel as it feared for the safety of the nursing sisters. Both the colonel-in-chief and matron had personally interviewed them a day prior and gave them the chance to leave Singapore on a ship.

One of the nurses, Brenda M. MacDuff, recounted her dreadful experience of the process. The morning before the attack, she received instructions from the matron, Violet Maud Evelyn Jones, to leave with her suitcase while she was dressing the wounds of Captain Henry Mills of the Armoured Cars Battalion. In a record of Brenda’s experience, she described how “the matron was crying, as she thought it was terrible to have to leave their patients behind.”

Nurse MacDuff was sent to board a local coasting steamer ship called the Kuala, set to depart Singapore that night, together with other nurses. There were 500 people on board, which included a large number of nursing sisters, army and government personnel, auxiliary staff, and Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD).

In the early morning of 14 February, the Kuala reached Pompong, a small uninhabited island about 80 miles southeast of Singapore. There, nurse MacDuff attempted to conceal herself with branches, but was sighted by a reconnaissance plane and hit directly by bombings.

The matron and several nursing staff members lost their lives before even reaching the island. Many were eventually interned in Sumatra and knew nothing of the fate of the men left at Alexandra Hospital. In September 1945, they were flown back to Singapore and billeted in the Raffles Hotel while waiting for ships to return them to the United Kingdom or Australia.

Peter de Lucy re-visited the site of the Battle of Kuantan, where his armoured car laid abandoned, in 1946. He was conveyed to Alexandra Hospital when he sustained battle wounds, and went on to survive the massacre.

Reunion was a turbulent ordeal for many families and individuals. Until the end of the war, Peter de Lucy was sent to work in the docks for the Japanese, unloading bombs from ships as they came into the Singapore harbour. During the long separation from her husband, the only news that Dorothy de Lucy received from him was a single postcard containing a few phrases from a pre-written list by the Japanese authorities.

Like many of their friends, the couple found it challenging to readjust to their new lives after the war, as they had lived in completely different circumstances for the last four years. While the men and former British soldiers had been put to hard labour in service of the Japanese troops, their wives who had evacuated Singapore resumed their ordinary everyday lives and even sought employment.

In the words of Dorothy de Lucy, “Women had been in authority and in positions of responsibility all over the world” while their husbands had been taken as prisoners by the Japanese. The events of the war had changed Dorothy and Peter de Lucy irreversibly. Yet against all odds, the couple reunited and rekindled their relationship upon returning to their home in Singapore.

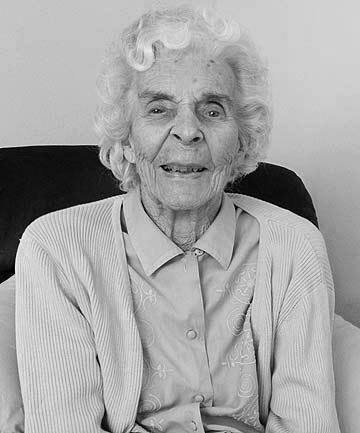

Mrs Brenda MacDuff was evacuated from Singapore right before it was invaded, and even survived the bombing of the SS Kuala. She went on to live up to a ripe old age of 105.

Although most women and children had been evacuated, there were still a number of Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurses left in the hospital, including Dorothy “Tommy” Hawkings. Believing that Singapore would remain invincible against the Japanese, she and her fiancé, Henry Francis ‘Peter’ de Lucy from the Armoured Cars Battalion, decided to get married on 7 February 1942, but were separated during the massacre at the hospital.

As bombing and shelling were rampant in Singapore, they had no time for invitations. They put up a notice in The Straits Times—which was being printed as usual—five days before the wedding, inviting all their friends and relations to a local cathedral at two thirty in the afternoon.

Food shortages made it difficult to prepare a wedding cake, but the Bishop of Singapore helped make one out of currants using a baby’s bathtub in his air raid shelter. For the de Lucys, it was a perfectly beautiful wedding, followed by a reception attended by a contingent straight from the front line, some with arms bound up and others with mud on their trousers and boots. Unfortunately, many of them did not survive the massacre.

After their wedding, Peter de Lucy was taken back to his regiment and Dorothy de Lucy continued her work at the hospital. She was evacuated from Singapore by ship a day before the massacre took place. Just as she left the hospital, her husband, wounded during the Battle of Kuantan, was sent there because of his injured arm. As the wards were full, he was put in a storeroom with other walking wounded. He survived the attack since the Japanese did not enter the room, believing that it was used as a storage cupboard. His compatriot in the same armoured car, Corporal Robert Veitch, was less fortunate, meeting his end on the operating table via Japanese bayonet.

The Japanese prisoner-of-war index card ascribed to Peter de Lucy, who was captured and imprisoned in Singapore until the end of the war.

Postwar Recovery

As we pay tribute to and commemorate those who fought and lost their lives during the massacre, celebrating their humanitarian spirits and feats of bravery, a part of bringing closure to the tragic event lies in seeking justice for these victims.

It was recorded in documents from the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE) — which began in 1946 in Tokyo, Japan — as well as other literary scholarship that the Japanese soldiers were tried for their war crimes after World War II while housed in Sugamo Prison in Yokohama. In September 1946, a British colonel named Cyril Hew Dalrymple Wild testified against the Japanese at the IMTFE for the massacre at the BMH.

In addition to the massacre, Wild’s testimony covered the initial Japanese landing at Kota Bharu, the mass shootings of young Chinese men in Singapore, and his experiences at the Burma–Thailand Railway. Lieutenant General Renya Mutaguchi and General Tomoyuki Yamashita, who both commanded the 18th Division of Japanese troops that arrived in Singapore from Malaysia in December 1941, were interrogated about the events that took place at the hospital.

The buildings of the hospital were only fully reinstated years after the war. This photo from September 1945, a month after the liberation of Singapore, shows prominent marks of damage sustained during the invasion.

Lieutenant General Mutaguchi was identified by Captain Richard Waller as the Japanese commander who visited the BMH. Mutaguchi was later released from prison in 1948, after the tribunal found insufficient evidence needed to charge him and his subordinates with war crimes.

The hospital was reclaimed by the British and continued to serve the British military after the Japanese surrendered in August 1945. It was a hub for postwar recuperation and housed medical officers; injured servicemen and British military soldiers made up 90 percent of its patients.

The development of Singapore’s healthcare system was disrupted by World War II. Malnourishment was rife, the infant mortality rate was high, and infectious diseases continued to be widespread.

The colonial government aimed to restore the public health system and the health of the general population back to pre-war levels by the late 1940s.

During its transition back to the British Administration, the hospital lacked the necessary equipment, medical and nursing staff, and specialists. There was a dire shortage of water. Nora Irvin, a member of the nursing staff stationed at the hospital after the war, noted that “several doctors stole cutlery and other things from the Adelphi Hotel, and helped themselves to some equipment for the patients.” The hotel was abandoned and unoccupied at that time but was located in an area under British Military Administration.

In 1946, reinforcements were sent from England to the hospital. Among them were nurse Nora Irvin and Alan Boon, a radiographer for the British Military during the war.

Boon began his military career when he was 19 years old and was first dispatched as a radiographer to the 102 Field General Hospital unit in the north of England. After several postings across Europe, India, and Southeast Asia, he found himself in Singapore at the end of the war, after the Field General Hospital had disbanded. While wandering around Singapore to look for a hospital where he could be onboarded as a radiographer, Boon found the BMH and made the decision to approach it, explaining that “it was the first one I found, and I walked in and that’s where I was commandeered.” Much to Boon’s surprise and delight, his arrival was most opportune for him and the hospital. They told him, “Sit down, you’re not going away from here now. I’ve got you.”

From February to August 1946, Alan Boon worked in the extremely modest radiology unit, which consisted of an English radiologist, an Indian radiographer, a Pakistani darkroom assistant, and two sweepers. However, the radiographer was grossly overdue for his leave in India.99 In two weeks, Boon learnt the ropes at his new job. After the radiographer left, Boon became the only radiographer in the BMH, often working late into the night and at times sleeping outside the X-ray room.

He kept administrative records of patient cases and took, based on the doctors’ instructions, radiography films and pictures, which were developed for the radiologist to make diagnoses and medical reports. Boon recounted that “any accident that happened after office hours were called emergencies and just had to be done at that time. They needed the X-ray. You always had to have one on duty.” As such, while he was accommodated with other military personnel in a barracks room, he often chose to sleep outside the radiology room to not wake his bunkmates when he was needed for an emergency radiography session during the night.

The picture on the left shows Corporal Alan Boon on the MS Maetsuycker, which took him to Singapore in 1946.

Boon would join the radiography team here at BMH Singapore by a stroke of luck, as a vacancy was opened for him when he arrived.

To alleviate the shortage of nursing staff, Nora Irvin was one of the many nurses deployed there for twelve months in 1946. Nurse Irvin helped with blood transfusion procedures and ward night duties.

However, general healthcare and medical procedures like blood transfusions were difficult to carry out due to the shortage in equipment and sterilisation tools. At that time, many staff members lacked formal medical training and would unknowingly perform medical procedures incorrectly. “I remember in those days, we used to warm the blood before we give it,” Irvin recounted in a slightly troubled tone. “And that was the worst thing you could ever do!”

The nursing staff, including Irvin, cared for a handful of female civilian patients who came from internment camps in Java and Sumatra. Many of these women were severely malnourished and some were in a state of trauma. Diets and food intake were the primary concerns with regards to these patients.

“There were patients who had been in camp [whom] we fed wrongly,” Irvin shared, recalling another medical mishap. “Later, fellows who came out of camp were very well fed in a graduated way, whereas we gave them too much in the beginning and that didn’t do them any good.”

The RAMC returned to BMH Singapore in 1945, under the command of Lt. Col. W.C. McKinnon.

Following her time at the British Military Hospital, Irvin became an instructor at the Singapore General Hospital, using her expertise to train young nurses.

Everyday life and recreational activities at the hospital gradually resumed, and a sense of normalcy was restored. Morning conferences and prayer meetings were held regularly. The cookhouse was back in operation, and the cooks even made a hollow pit in the ground near it for slaughtering chickens.

On Christmas Day and other holidays, the doctors, nurses, and patients went to the field to play football. Medical personnel like radiographer Boon and members of the RAMC would play against the Royal Engineers in friendly matches.

“I remember someone took a picture of me in my football kit, with my designed shirt and shorts, and socks and football boots. We played the Royal Engineers and I seem to remember the match ended in 1-all,” Boon related fondly. Ghosts were, surprisingly, never sighted by any witnesses and rarely mentioned at the hospital.